A lot can happen in 100 years. And the last 100 years has seen unbelievable technological and societal change, both in the UK and across the developed world.

If you are over 50, and grew up in Birmingham, then you may have some idea of what life in the city was like in 1920, due to stories related by grandparents (or parents, depending on your current age).

For many living in Birmingham in 1920, it was a time of grief and hardship. The terrible loss of so many lives during the First World War, and the devastating impact of the widespread Spanish flu virus in 1918 meant that families and individuals all over the city were working at rebuilding their lives, homes and workplaces at a very difficult time.

If you have ever watched the TV drama series Peaky Blinders, you will be familiar with the writer’s vision of 1920s Birmingham as a hotbed of angst, violence, squalor, grime, smog, and poverty.

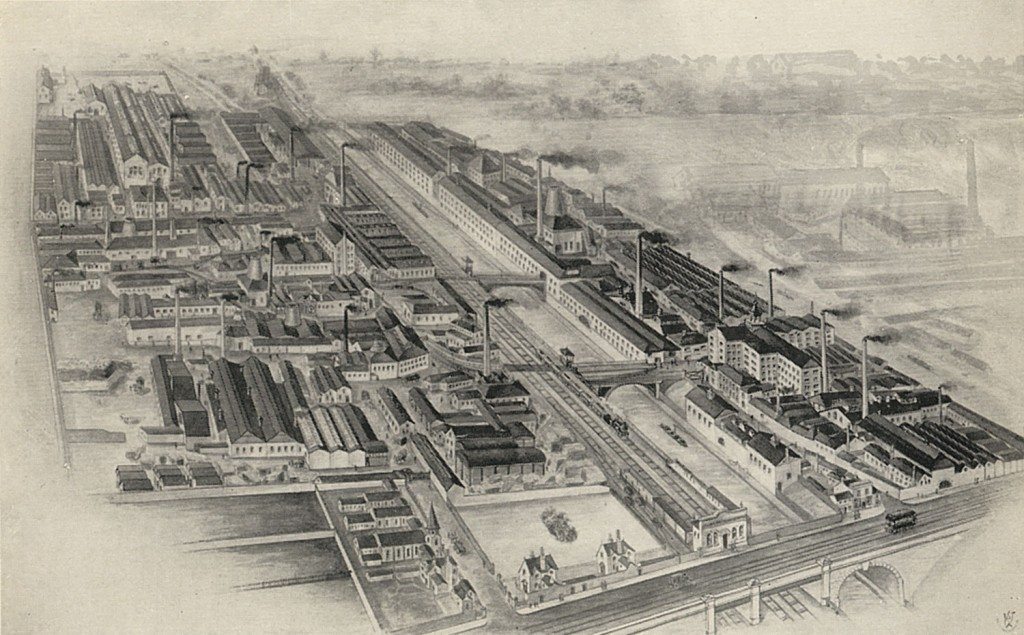

However, on the flip-side, the drama also portrays the city as the proud and rightful heart of Britain’s industrial revolution. Widely known as “the city of a thousand trades”, Birmingham led the way when it came to manufacturing, as well as many other trades and industries.

Its factories and workshops were the lifeblood of the city, as tens of thousands of workers produced an array of ground-breaking products which were shipped around the world. Some of those product brands became etched into our national identity, and although many have ceased to exist, there are a few that remain hugely popular to this day.

By 1920, the city had become a leading producer of metalware, guns, ammunition, jewellery, toys, motorcycles, cars, tools, utensils, pen nibs and watches, and it was also a major centre for printing. By this time, Birmingham was known the world over for its industrial innovation.

So, which factories actually existed in Birmingham in 1920, and what became of them?

Fort Dunlop

The world-famous Dunlop Tyres company opened its first factory premises in Erdington, in 1917. The factory was housed in a Grade A listed building, and the site on which it stood became known as Fort Dunlop.

Demand for solid rubber tyres had risen significantly during the First World War, with the increased production of vehicles such as lorries and trucks as part of the war effort.

After the war, the demand for Dunlop’s tyres continued, due to the rapid expansion of the motor industry.

Fort Dunlop was the biggest factory in Birmingham during the 1920s. By the 1950s, Fort Dunlop employed more than 10,000 workers, and at one time it was the biggest factory in the world!

Later, Dunlop Tyres were Formula One’s top choice for their racing cars, and the brand was associated with the very first car to exceed 200 mph.

However, the demand for Dunlop tyres declined during the 1980s as the number of car imports rose significantly, and the Birmingham factory was subsequently closed.

The Fort Dunlop site was left derelict for 20 years, before being developed and repurposed, reopening in 2006 as a complex of offices and a Travelodge hotel boasting a grass roof, complete with models of giant cows!

The Wolseley Tool and Motor Car Company

The Wolseley Tool and Motor Car Company was Britain’s largest car manufacturer, and their factory site at Adderley Park had seen rapid expansion by 1920, increasing six-fold due to its work for the war effort. During the First World War, car production at Wolseley gave way to the production of armoured vehicles, munitions and aircraft components.

In 1918, Wolseley signed a contract with a Japanese company, giving them exclusive production and marketing rights for Wolseley products in the Far East. Several Wolseley employees were sent over to Japan to assist in setting up the operation and, in December 1922, the first Japanese-built Wolseley model entered production.

In 1926, Wolseley was bought out by William Morris, who proceeded to restructure the business, moving most of its operations to his Ward End plant in Washwood Heath, where engines for the original Morris Minor were produced. In 1935, Wolseley became a subsidiary of Morris Motors Limited.

The British Small Arms Company (BSA)

The BSA factory had taken a hiatus from producing motorcycles during the First World War, and the company had returned to its gunsmith roots to focus on the mass production of small arms and ammunition. Between 1914 and 1918, their operations were expanded throughout the city as part of the war effort.

A number of Peaky Blinders storylines are focused around the BSA, since the main factory was situated in the Small Heath area of Birmingham, near to where the Peaky Blinders characters were presumed to be living.

The factory was built on part of the 25 acres of land purchased by the company, and the site also included a new road which was constructed for the sole purpose of gaining access to the factory buildings. The road was named Armoury Road, and it still exists today.

During the Second World War, production of firearms and ammunition was scaled up significantly, and by mid-1940 employees were working a seven day week. At this time, the BSA was producing 50% of all the precision weapons manufactured in the UK.

Unsurprisingly, the BSA premises were identified and marked out as prime targets on the maps issued to German bombers. The main sites at Small Heath and Sparkbrook were heavily bombed several times during the course of the war.

Bombs dropped during a heavy air raid on 19th November 1940 left the main factory very badly damaged, temporarily halting production and trapping hundreds of workers. 53 employees were killed, and 89 were injured. Two brave male employees later received the George Medal for helping to save the lives of some of the trapped workers.

Following the Second World War, the BSA focused mainly on the manufacture of bicycles and motorbikes. A number of company mergers and takeovers ensued over the next two decades, and the factory finally closed its doors in 1972. Today, the site houses several warehouses and other small businesses.

Cadbury’s Chocolate

In 1878, the Cadbury family purchased a 14.5 acre estate on which to build their brand new chocolate factory. The Cadbury family were devout Quakers who believed that workers should be looked after, and they began building homes on the estate for their employees. This later became the village-within-a-city district of Bourneville.

In 1920, the Cadbury Dairy Milk range became purple and gold – the colours we have come to associate with the brand ever since. Before this, Dairy Milk was pale mauve with red script, and packaged in a continental style ‘parcel wrap’.

The Cadbury Flake was also launched in 1920, and was originally packaged in a see-through wrapper. The yellow wrapper we have become accustomed to didn’t come into being until 1959.

Despite a number of subsequent mergers and takeovers over the past 100 years, the Bourneville factory is still the main production site for the Cadbury brand today, and it is the second biggest confectionary brand in the world. The company is currently owned by the American corporation, Mondelez International (formerly Kraft).

The HP Sauce factory

In 1920, the factory that produced HP Sauce factory was known as the Midlands Vinegar Company, and was situated in the Aston district of Birmingham.

It is thought that the name HP was inspired by the Houses of Parliament, as a restaurant nearby served the sauce to its diners – hence the famous, iconic image on the bottle’s label.

In December 1956, the HP Sauce factory was in the news for all the wrong reasons. A 15,000 gallon vat of vinegar had exploded, resulting in rivers of vinegar flooding the nearby streets and people’s homes. Allegedly, the force of the vinegar current was so great that furniture from local residents’ homes in Tower Road was swept down the hill as far as Aston Road, almost a quarter of mile away.

The HP factory remained in Aston until 2007, when its parent company Heinz (who had purchased HP Foods in 2005) moved production to Elst in the Netherlands. The factory building was subsequently demolished, and a large cash and carry store was built in its place.

Bird’s Custard factory

The Bird’s Custard factory in Digbeth produced the custard that was regularly served to the allied armed forces during the First World War.

Bird’s was a pioneer in the use of promotional items and colourful advertising campaigns. The famous three bird logo wasn’t introduced until 1929, however.

Bird’s operated out of its factory in Digbeth until the company moved its operations to Banbury in 1963, but the brand’s legacy has lived on in Birmingham ever since. The original custard factory in Digbeth (still known as The Custard Factory) first became an arts and media production centre, and is now home to a plethora of quirky independent shops and creative businesses.

The Typhoo Tea factory

Typhoo Tea was launched in 1903 by Birmingham grocer and businessman, John Sumner. It is thought that Sumner’s sister had told him about tea fannings’ relaxing effects, which prompted him to create his own unique blend to sell in the family’s grocery shop.

The name Typhoo was taken from the Chinese word for “doctor”. The tea was marketed as a health aid to help cure anxiety and indigestion, due to the perceived calming effects achieved when using the tips in the blend.

By

the 1920s, Typhoo had opened a factory in the Digbeth district of

Birmingham, and in 1926 John Sumner’s son took over the running of

the business. The factory was bombed during the Second World War, and

production was moved to other sites around the city.

In its heyday, the brand devised a number of well-known advertising slogans and jingles, perhaps the best known of these being, “You only get an OO with Typhoo.”

In 1968, the company was sold to Schweppes, which later merged with Cadbury, to become Cadbury Schweppes. The main Birmingham factory eventually closed in 1978, as it was unable to compete with other brands who had adopted modern high-speed production methods. Production was moved to Liverpool, where Typhoo tea is still manufactured today.

The Lucas factory

In 1914, Joseph Lucas Ltd. (later known simply as Lucas) signed a contract with Morris Motors Limited, to supply them with electrical equipment. During WW1, Lucas also produced shells, fuses, batteries, and other electrical equipment for military vehicles, as part of the war effort, from their factory at Great King Street in Hockley.

After the war, Lucas opened a larger factory site in Formans Road, Tyseley, and the company expanded further when it signed an exclusive contract with Austin in 1926. During the same year, Lucas found itself at the centre of a furore during the national General Strike, in which almost two million workers downed tools. Factory worker, Jessie Eden (a real-life person cast as Tommy Shelby’s lover in Peaky Blinders) was a shop steward and self-confessed Communist, who became well-known across the country for leading thousands of male workers at the Lucas factory out on strike. In 1931, she also led 10,000 women workers out on a week’s strike, which pioneered a mass movement towards trade union membership for women.

Lucas later acquired many of its British competitors, and by the mid-1930s the company practically had a monopoly as a producer of automotive electrical equipment in Britain.

Lucas subsequently became the principal supplier of motor vehicle engine parts to British manufacturers such as BSA, Norton and Triumph, and rapidly expanded into new areas all over Birmingham and the rest of the UK. Generations of Birmingham people worked at the original Tyseley factory site throughout the twentieth century.

In 1996, Lucas merged with the American Varity Corporation to form LucasVarity PLC.

The old factory at Formans Road, Tyseley was demolished in 2006, and the site is currently undergoing a £40million regeneration, as it is transformed into an industrial park.

Over the decades, most of these factories have closed their doors, and they have been either demolished, developed or repurposed. However, they have all left their mark, both on the city landscape and in the memories and hearts of the people of Birmingham.