In recent years Carl Köhler (1919 – 2006) has gained recognition, particularly for his psychologically charged portraits of distinguished writers, artists, composers and musicians. Bordering on abstraction, these portraits reveal the expressive powers of Kohler, who used a variety of media and styles to capture each subject’s presence, personality and “poetic dimension”. His late works show an artist further reducing and abstracting the human form in his search for immutable identity.

Köhler was a neo-modernist painter, who practised and exhibited in leading circles of Swedish art during the 20th century. He studied at the Swedish Royal Academy of Art from 1945-1951, where he was taught by one of the great Swedish modernists, Sven “X-et” Leonard Erixson. During this time he exhibited paintings at Färg och Form, a contemporary gallery in Stockholm, which Erixson had founded to showcase the radical works of the neo-expressionist painters, who were experimenting with a new form of art defined by its decorative, colourful and freely executed style.

Recognised early on for his artistic talent, Köhler was awarded numerous state scholarships, which allowed him to travel far beyond Sweden to Norway, Egypt, Spain, and France. Most significantly, in 1951 he travelled to Paris, which at this time was the centre of the Western art world. It was in Paris that he was introduced to the Cubist works of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Intrigued by their Synthetic Cubism, Köhler began to experiment with the possibilities of collage as an aesthetic of modernity, assimilating this technique into his own practice.

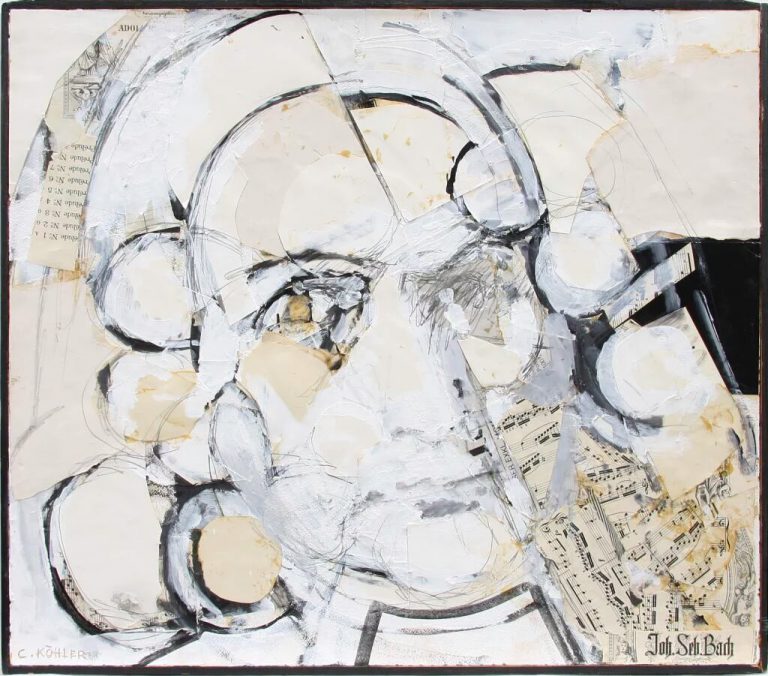

In his oil collage of Johannes Sebastian Bach (c.1990) he has wittily incorporated Bach’s sheet music and typeset initials, which become an intrinsic part of the rhythmic composition. Intersecting circles, which represent his curled hair, also cleverly signify the shape of musical notes. Köhler painted numerous other composers, including Sibelius, Mahler, Mozart and Stravinsky. The artist’s mother, Lisa Köhler, was a well-educated concert-hall singer, who instilled in her son a love for classical music, ballet and the theatre. Köhler’s son, Henry, recalls that, “the old gramophone was always playing classical music on a very high volume in my father’s studio while he was working”.

A literary enthusiast, Köhler also depicted many distinguished writers, including Virginia Woolf, Jean Cocteau, and Simone de Beauvoir. Köhler created visual manifestations of their works that he had read in a series of ‘authorportraits’, which have recently been part of solo retrospectives across America. One of the most striking examples is a mixed media portrait of the avant-garde writer Samuel Beckett (c.1990). With pencil and ink on paper, he has mapped out with rough strokes, reminiscent of Egon Schiele’s expressive line, the creases of the author’s face, and his notoriously dishevelled haircut. There is a fragility to this fragmented portrait, which deconstructs the writer into his creative essence. As Köhler explained, “Maybe I am looking for the overtones of a visage, the poetic dimension.”

Another exceptional portrait is James Joyce – Getting Blind, executed around 1995, which belongs to Richard Hugo House in Seattle. This haunting India ink collage drawing takes as its subject the author of Ulysses, and his tragic loss of sight. There is a gestural quality to this work; as Michael Upchurch, the Seattle Times arts critic points out, “ink, splattered and sponged onto the uneven paper surface, pushes toward abstraction. Yet it nails the figurative basics: Joyce’s wire-brush moustache, his Coke-bottle-thick glasses, his thin tapering chin”. It seems as if Kohler was searching, through his medium, to uncover the essence of Joyce’s creativity, which is as much a dark power, as it is brilliant.

Köhler always varied his artistic style to match the subject. In his evocative oil painting of Fyodor Dostoyevsky (c.1990), his dramatic and Rembrandt-esque use of chiaroscuro imbues the ‘authorportrait’ with an emotional intensity. Again, he has characterised the writer by an aura of darkness; troubled, pensive eyes reveal an author who explored human psychology within the uneasy atmosphere of 19th-century Russia.

Meanwhile, in his portrait of Franz Kafka (c.1985), he has used a woodcut, lined with heavy black ink, to show the powerful psychological presence of the dramatist famed for The Metamorphosis. The art critic Emily Colette Wilkinson writes poignantly about this work:

“The longer you look at the portrait, the more it seems to represent the carapace of an insect, or a skull, or a snarled, unreadable web—all symbols of the Kafkaesque, with its the atmosphere of impending danger and death, its sense of menacing, disorienting complexity, of something becoming something else”.

Whilst recent exhibitions on Köhler have focused on his emotionally charged ‘authorportraits’, there is also a compelling power to his later works, in which he further abstracted the human form. His paintings, created from the 1990s onwards, are defined by reduced and simplified figures, which clearly evidence the influence of Matisse. Many of the Swedish modernists went to study at the Académie Matisse in Paris, and returned to their native land, influenced by the decorative and colourful Fauvism of the French artist. Köhler was very much interested in Matisse’s elegant outlines of the female form. The movement and fluidity of the simplified bodies in works such as Theatre Bodies (c.1990) and Dance-Couple (c.1995) echo the figures in Matisse’s masterpiece La Danse (1910).

Another oil painting, Petrushka Alone (c.1995), depicts the main character from Stravinsky’s ballet Petrushka, which tells the story of the loves and jealousies of three puppets. The ballerina’s body is achingly poised en pointe, and shows Köhler abstracting the figure to her essential shapes with a real energy and eloquence, in a synthesis of art and music. This striking image was notably chosen to be part of the art work for When Music Worlds Collide, an album that is part of Jay Z’s TIDAL Rising program.

Köhler was undoubtedly one of Sweden’s great Neo-modernist artists, whose recent recognition is well-deserved. In his varied portraits of fellow artists, writers, dancers and composers, he has used his expressive powers to etch out the landscape of each subject’s face and figure. More importantly, however, from within his abstracted intersection of shape, and nuances of line, Köhler shows that what really matters is beneath the surface. He distils the essence of his subjects to capture their intrinsic identity, celebrating creativity in all its varied forms.

Over the last few years retrospectives of Köhler’s portraits have been held in prestigious libraries and cultural venues across the United States and Canada. Kohler’s work can also be found in private collections and public museums around the world, including the Nationalmuseum, Stockholm; Gothenburg Museum of Art; and Gallery Voksenåsen, Oslo. For more information, please visit carlkohler.com.

With special thanks to Henry Köhler, who manages his father’s estate, and provided all images.

Article by Ruth Millington http://ruthmillington.co.uk/

Reviews are disabled, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.