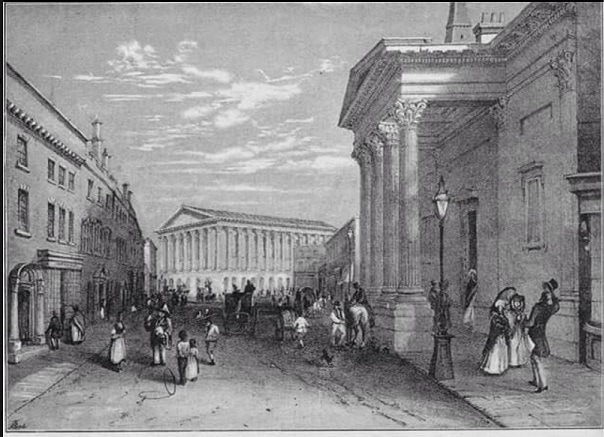

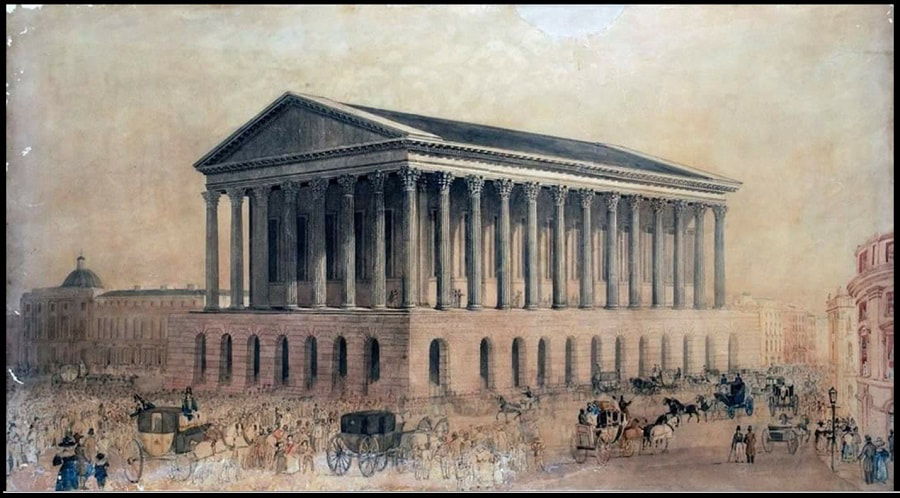

Charles Dickens visited Birmingham Town Hall to read his Christmas Carol to a couple of thousand people, eager to hear one of the most notable literary geniuses of the time.

It was the first public reading of Christmas Carol and one which he no doubt saved for one of his favourite places. The following description from the Birmingham Journal in December 1853.

What a grand, fine looking party it was. The lights were so brilliant and the drawing room so gay, and the holly so tastefully wreathed that there could be no mistake about this being Christmas. Then the host himself arrived and took his place in his big armchair and told us that we may laugh and cry as much as we wanted, as he liked nothing better than a lot of sympathy.

“The good people of Birmingham”, reported Dickens to a friend, “seemed to understand everything, respond to everything, and misinterpreted nothing. I felt as if we were all bodily going up into the clouds together”.

Dickens made use of a row of overhead gaslights to act as spotlights during his reading, an invention closely associated with the city. In 1797, William Murdoch was the first to exploit the flammability of gas for the practical application of lighting. He worked for Matthew Boulton and James Watt at their Soho Foundry steam engine works in Birmingham. In 1798, he used gas to light the main building of the Soho Foundry and in 1802 lit the outside in a public display of gas lighting, the lights astonishing the local population – public street lighting with gas was later demonstrated in Pall Mall, London, on January 28, 1807.

Apart from Charles Dickens giving readings in Birmingham Town Hall he was the sixteenth President of The Birmingham and Midland Institute, here are a few exerts from his readings.

Taken from his first speech in 1844:

“Birmingham is, in my mind and in the minds of most men, associated with many giants; and I no more believe that this young institution will turn out sickly, dwarfish, or of stunted growth, than I do that when the glass-slipper of my chairmanship shall fall off, and the clock strike twelve to-night, this hall will be turned into a pumpkin.”

“I found my strong conviction, in the second place, upon the public spirit of the town of Birmingham—upon the name and fame of its capitalists and working men; upon the greatness and importance of its merchants and manufacturers; upon its inventions, which are constantly in progress; upon the skill and intelligence of its artisans, which are daily developed; and the increasing knowledge of all portions of the community. All these reasons lead me to the conclusion that your institution will advance—that it will and must progress, and that you will not be content with lingering leagues behind.”

After a gift of a ring by the people of the town in January 1853:

“I shall remove my own old diamond ring from my left hand, and in future wear the Birmingham ring on my right, where its grasp will keep me in mind of the good friends I have here, and in vivid remembrance of this happy hour.”

In December 1853:

“I have seen in the factories and workshops of Birmingham such beautiful order and regularity, and such great consideration for the workpeople provided, that they might justly be entitled to be considered educational too. I have seen in your splendid Town Hall, when the cheap concerts are going on there, also an admirable educational institution. I have seen their results in the demeanour of your working people, excellently balanced by a nice instinct, as free from servility on the one hand, as from self-conceit on the other… Gather up those threads, and a great marry more I have not touched upon, and weaving all into one good fabric, remember how much is included under the general head of the Educational Institutions of your town.”

1869:

“Well, ladies and gentlemen, my heart has all been in my subject, and I bear an old love towards Birmingham and Birmingham men. I have said that I bear an old love towards Birmingham and Birmingham men; let me amend a small omission, and add “and Birmingham women.” This ring I wear on my finger now is an old Birmingham gift, and if by rubbing it I could raise the spirit that was obedient to Aladdin’s ring, I heartily assure you that my first instruction to that genius on the spot should be to place himself at Birmingham’s disposal in the best of causes.”